Customer Services

Full description not available

P**S

Not Only in Our Imagination

I had never heard of Alejo Carpentier before I read "Journey to the Seed," a story of his in The Oxford Book of Caribbean Short Stories, translated from Spanish by Jean Franco. Then I had to find more of his work. I first read "The Kingdom of this World," a magical, deeply emotional story set in Haiti just before and during the Haitian revolution. Next, I read The Lost Steps, originally published in 1953 and translated from Spanish in 2001 by Harriet de Oni. It's a very different story, of a man whose alienation in the modern world leads him to travel to the Orinoco in Venezuela to see for himself another world that still exists, not only in our imagination. I won't say anything more: read it for yourself.

W**G

A Latin America novel of incredible richness

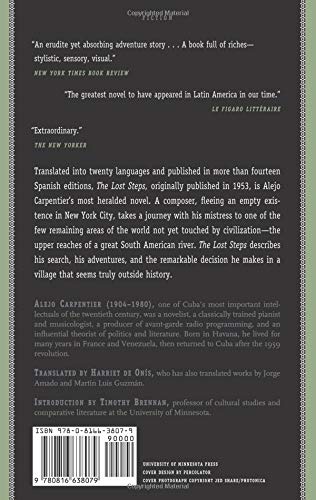

Probably the most remarkable literary event of the 20th century was the explosion--no other word will suffice--of Latin American literary creativity, fully comparable to a similar explosion in the US in the 19th century. And one of the most remarkable creators of this explosion is Alejo Carpentier. Reasonable people may differ regarding who is the greatest Latin American novelist, but surely Carpentier must be ranked among them, and "The Lost Steps" is his most widely read work.The plot of "The Lost Steps" can be summarized very simply. The narrator, a naturalized American citizen living in New York City, once had youthful ambitions to become a composer. However, he now finds himself earning a living doing musical hack work, e.g., jingles for TV commercials. He is married and also has a mistress. When the novel opens, he has not had any work commissioned in a while and is starting to feel desperate. A friend who is a museum curator offers him the opportunity to go to an unnamed South American country to find a rare musical instrument. The narrator cynically sees this as an opportunity to have an expenses-paid trip with his mistress, but as the trip progresses he feels his dormant musical creativity being revived. He eventually finds the instrument he is looking for. He also meets a primitive, illiterate, mixed-race young woman by whom he is initially repulsed but with whom he eventually falls in love and cohabits with. His mistress leaves him and goes back home. He ends up living with his mistress in a small, inaccessible village deep in the jungle; the only other inhabitants are a native tribe and a few merchants of European descent. He believes that he has now found true happiness, away from the corruption and decadence of modern civilization. He forgets all about his obligations to the museum that sponsored his trip and vows never to go back.One day his idyllic bliss is shattered when a helicopter lands and he learns that his "disappearance" has become front page news in the US. His wife and his museum sponsors have sent a search party to look for him. He realizes that he has no choice but to go back, although he desperately wants to stay. He promises his native lover that he will be back as soon as he can. When he gets back home, he discovers that he has become a celebrity, at least for a while, but he is miserably unhappy. His pregnant wife files for divorce, and the newspaper that sponsored his rescue now regards him as a traitor and deceiver and portrays him in the most negative light possible. His sources of income dwindle. He is reunited with his mistress but is repulsed by her and wants desperately to return to the village.Nearly a year passes before he is able to attempt to get back to the remote village. Getting there involves a water passage, and he finds to his horror that the rains that have fallen in recent months have caused the water level to rise to the point that the river covers the steps that were his marker for the jungle path to the village. He has no way to return to the village! Shortly thereafter he learns from someone who occasionally visits the village that his primitive lover has married someone else in the village. He is devastated. He suddenly realizes that he was never accepted by the people of the village or by his lover, that he was always regarded as an outsider who was only there temporarily and would never stay. Reluctantly, he decides to return to New York, realizing that he has no other choice.This simple synopsis does not to justice to the richness of this novel. Even in translation, the richness of Carpentier's prose comes through: his fluency with words, his mastery of sentence structure, his mastery of metaphor and allegory. This is a novel of immense erudition, replete with literary and musical references. One of the novels messages, I think, is to enjoy and savor the peak experiences of life when you can, because they won't last and they won't come back again. Another message is that perfect happiness is unattainable and that most humans need to be content with what they are able to attain. In short, this is a work of incomparable richness that I can recommend unreservedly.

T**S

incredible

First, anyone who criticizes this book for being pretentious and somehow hypocritical COMPLETELY misunderstands it. The irony that permeates almost all of the narrator's criticisms should be enough to tell you that this is not the case. The main theme of the work is the futility of the human will before the passage of time, amongst other subthemes that are wonderfully woven in. This is an absolutely beautiful book whose power brought me to tears a few times. I've read both the spanish and english versions and Onis's translation is very very well done-almost to the point that I enjoy her version more than the original. But, anyway, pick up this book, you won't be disappointed I promise you.

A**S

Five Stars

It has been one of my favorite books in English and in Spanish!!!

D**E

Retracing One's Steps

One of the great stylists of Spanish prose, Alejo Carpentier published six novels and three novellas between 1933 and 1979. He is primarily known for the novella _The Kingdom of This World_ (1949), the novel _The Lost Steps_ (1953), and the short story “Journey Back to the Source” (the literal translation would be “Journey to the Seed”), but his entire body of work deserves attention. For me, the portal into his narrative world was _The Kingdom of This World_, a fascinating chronicle of the Haitian revolution that does not have a real protagonist. _The Lost Steps_ is different, as it follows the adventures of a single nameless character who also narrates the story. The language, by itself, makes this one of the greatest Latin American novels ever written.The novel opens in London, and it is obvious from the first pages that our narrator is jaded and in need of a change of air. His existence has become humdrum, and he finds no satisfaction in his work, friendships, or married life. When he is commissioned to travel to the Latin American jungle in search of an autochthonous musical instrument, he seizes the opportunity to break away from the constraints and the quiet desperation of the modern metropolis. He will not travel alone, but in the company of Mouche, whom he describes as a friend but is in fact more than that. Their arrival in an unnamed Latin American country is immediately followed by a violent revolution, but eventually they embark on their search, meeting typical characters along the way: a Greek miner who carries with him a copy of the _Odyssey_, a priest, a herbalist, and the beautiful Rosario. Their journey mirrors the “discovery” of the American continent, and as they enter the primordial jungle they experience the passions, impulses, and desires that are latent in the human heart.Carpentier’s prose is meant to be savored. I read _The Lost Steps_ in its original Spanish, and then sampled the English translation by Harriet de Onís (who also translated _The Kingdom of This World_). It is unnecessary to point out that nothing replaces the original, but both versions afford great pleasure to the reader. I often found myself reading the text out loud, enjoying the exquisite texture of the prose, to the extent that sometimes I would lose track of the meaning, the mere sounds and the rhythm were so enthralling.As I read _The Lost Steps_, I could not help thinking about Joseph Conrad’s _Heart of Darkness_, which is one of my favorite novellas. I don’t think it an exaggeration to consider Carpentier’s novel a rewriting/expansion of Conrad’s novella, nor does this reading subtract from the merit of _The Lost Steps_. The protagonist is English. He travels to the heart of a wild land, where he comes to learn more about himself. His return to England is marked by the inadaptability of the person who has come face-to-face with the darkness inside him: one cannot simply go back home after an experience like the one described in these works. To read _The Lost Steps_ (and _Heart of Darkness_) is to penetrate the thick jungles of language, history, and the human psyche.The narrator is shaped by his journey, and delineated for us by his interactions with the three women in his life. Ruth, his wife, is an English actress who does not mind playing the same character over and over again; to the narrator, this reflects the monotony that characterizes their marriage. Mouche is the quintessential liberated French woman, in this case with an interest in astrology. The narrator uses her to satisfy himself, and he considers her trade to be nothing but a scam. Rosario, finally, is the local woman, the woman who has not been molded by European rationalism. I mentioned the influence of Conrad before, as a positive aspect of _The Lost Steps_. It can also be a negative aspect. I’m afraid the three women in Carpentier’s novel are caricatures. Or perhaps it is simply the narrator who perceives them as such. It really is difficult to care about this narrator. _The Lost Steps_ is, among other things, an existential novel; as is the case with other existential heroes (e.g., Roquentin from Sartre’s _Nausea_), I don’t think the reader is meant to sympathize.García Márquez was, as you surely know, a proponent of “magical realism.” Carpentier had his own thing: the “marvelous real.” The difference between the two? We can turn to Carpentier himself for an explanation. In the prologue to _The Kingdom of This World_, he complains about the appropriation of the marvelous by European artistic movements such as surrealism. (Let us keep in mind the interest of the surrealists in “primitive” art and cultures.) In the American continent, the marvelous manifests itself constantly. It is not an aesthetic quality, but an ontological one. A similar border separates magical realism from the marvelous real. The former may not be as “fake” as surrealism, but the latter is more genuine, even if it is less colorful and fascinating. (No one ascends to heaven in Carpentier’s works, for instance.)_The Lost Steps_ is focused on language and reflection rather than storytelling or plot. I was reminded of two Argentinean novels that may bear the influence of Carpentier, at least stylistically: Antonio Di Benedetto’s _Zama_ (1956) and Juan José Saer’s _The Witness_ (1983). The former is set in the 18th century; the latter, in the 16th century. Both are available in English and worth your time if you’re interested in the New World as seen by European eyes.As much as I enjoyed _The Lost Steps_, I believe _The Kingdom of This World_ is superior and a better place to start with Carpentier. As a novella, it is more manageable. In its structure, it is more experimental than _The Lost Steps_. It is, finally, just as good an example (perhaps even a more satisfying one) of the marvelous real. In any case, I would read these two before venturing into _Explosion in a Cathedral_ (1962) or _Reasons of State_ (1974). The former is a historical novel about the Caribbean during the French Revolution, while the latter is Carpentier’s own attempt at the “dictator novel,” to be placed on the same shelf as García Márquez’s _The Autumn of the Patriarch_ (1975), Roa Bastos’ _I, the Supreme_ (1974), Asturias’ _El Señor Presidente_ (1946), and Vargas Llosa’s _The Feast of the Goat_ (2000).Try this experiment: open any Carpentier novel at a random page and read that page out loud. If you’re not captivated, you may move on to another author.Next on my list, from Carpentier: his debut novel, _Écue-Yamba-Ó_ (1933).Thanks for reading, and enjoy the book!

L**T

Chance isn't the same as fate

While I completely agree with the points made in the other positive reviews, I felt the role of chance in the structure of the novel robbed the work of a lot of its power.If we view the narrator as a tragic hero then we ought also to be able to say that his downfall is a result of certain character flaws, perhaps even that those flaws represent not just personal failings but an inability on the part of those from the modern world to truly comprehend a simpler existence. However, while these flaws do in some way lead to the narrator's fate, the magnitude of his despair is in no way a direct consequence of them. The specific events which sunder him so completely from the lost world are not the inevitable outworkings of his character flaws; they are simply chance, e.g. sudden lack of money, or a particularly high river.For me, the random factors behind the narrator's misfortune also deny the possibility of any grander conclusion along the lines of the inevitable incompatibility between a citizen of the modern world and a simpler civilisation. Instead I am left with a sense that his hubris is simply being punished by fate (and that's not capital-F Fate).And so finally, I'm afraid, I was left with a feeling more akin to the popping of a holiday romance bubble, which is a terrible slur given the otherwise excellent qualities of the book.

S**S

Further endorsement

Not much to add to the two extant and excellent reviews here. This is a minor classic. The language is angular rather than baroque. Carpentier obviously foraged on architectural dictionaries. At times you think the book is about to stall, but the utterly admirable translation keeps winning through and on a re-read there are some magnificent passages here. There's not much irony to offset the slightly dated attitude towards women or the equally dated sense of the innate superiority of the intellectual. The 'revelations' about the origins of music and the didactic aesthetic pale in the light of - say - Mann's 'Dr Faustus' or Broch's 'Death of Virgil' (both of which have arthritic qualities, too). If you like your (capital 'L') literature 'over-easy' (Scott Fitzgerald, say, or Garcia Marquez) then you won't care much for TLS; Carpentier tries harder and it shows in both a good way and a bad way. But I shouldn't be carping like this: I should be fainting with damn praise...

Trustpilot

1 month ago

3 weeks ago